Category: Planning

Being a pedagogical leader… and doors.

Pedagogical leadership is a tricky pursuit, so many nuances and complexities to navigate. While my wife and I were chatting about this the other day, the metaphor of doorways emerged… so I will try and put it into words!

It occurred to me that being a pedagogical leader means seeing a wide variety of doors in front of you and then knowing which ones to move towards, which ones to open, who to open them for and how much to open them by.

When guiding a team through unit design, for example, a pedagogical leader must make a series of choices. Having a well-designed and clear unit design process will already reveal which doors the team needs to go through in order to go deeper into the process, but the order in which those doors are opened is critical. Going through the first door must, of course, improve what happens when the next door is opened. It must be developmental, and logical. At times, however, teams encounter a locked door, or a door they can open but are struggling to get through, and a good pedagogical leader must handle that situation. Here’s some examples of situations in which that might happen.

Imagine a team has reached the point in the planning process where they must use the decisions they have already made in order to design a provocative initial experience, or series of experiences, they can use in order to give students the chance to reveal what they already know, think, understand or feel about the context . The pedagogical leader uses the unit design process to open up that door, ready for the team to start generating ideas, but the team is struggling to come up with any. In this situation, the pedagogical leader must open that door wider by sharing a few ideas of their own, by modeling the act of putting ideas on the table, by modeling creative thinking, by challenging the team to consider what is possible… and possibly even pushing those boundaries a little while they’re at it.

Imagine a team is exploring the content that they feel should shape the unit they are designing, yet they miss an area of the content that is obvious to the pedagogical leader and that could take the unit in a novel and interesting direction. The process has been designed well enough for them to see that door, move towards it and open it… but they just don’t (yet) think that way. Rather than let it slide, the pedagogical leader must nudge them towards that door, open it for them and describe what could lie on the other side… otherwise that opportunity could be missed.

Imagine a team is analyzing some student work so they can use the data they have gathered in order to make decisions about where to go next with the learning, and a pattern or trend becomes visible to the pedagogical leader but not to anyone else in the team. The process is designed to try and help the team to notice potentially powerful patterns and trends, but they just don’t (yet) see things that way. The pedagogical leader must point it out to them, describe it and open up the door that shows the team what implications for teaching and learning lie behind it.

Imagine a team has taken their unit design into a really good place and are ready to start thinking about the pedagogy that could really breathe life into what they have put on paper. However, when conversation turns to pedagogy, the pedagogical leader notices a worrying shift back to the pedagogy he/she is trying to move people away from. He/she can see, very clearly, the pedagogical moves that really would breathe life into then unit they have designed, but the team just doesn’t (yet) see the art of teaching that way. The pedagogical leader must open up that door for them and show them the practice that lies on the other side… he/she may even have to go into classrooms and show teachers what it looks like rather than just be satisfied with telling them.

I could go on coming up with examples, but I guess the main point I am trying to make is that pedagogical leadership involves, but is not limited to, the following interactions with doors.

- Knowing when people are stuck and how to generate and put ideas on the table that open doors for people and take them through to the next level.

- Knowing when people are limited by their own experience and how to nudge them towards and through doorways that push their boundaries and take them into new practices.

- Knowing when people are limiting what is possible for students and their learning and how to pull people through doors that reveal the variety of possibilities that young people deserve.

Photo by Nick Chalkiadakis on Unsplash

Why Bubblecatchers Matter

A few days ago, My family and I went for dinner at Anne’s house. Anne was one of my Mum’s closest friends when we lived in Tanzania in the 80s, and I haven’t seen her for 31 years. During the evening, I spotted a very nice notebook on the coffee table in front of us… “nice Bubblecatcher” I said.

“Ooooh yes… Bubblecatchers!” Anne replied with incredible enthusiasm.

It turns out that, for many years, Anne has shown her students at the International School of Tanganyika – and her students in the school she works in now – the video of my Learning2 talk in which I shared the story and concept of Bubblecatchers.

As we talked about how she has used them, I was reminded – again – of their profound importance, of the many nuanced habits that they encourage, of the way they can change and enhance relationships with writing for all sorts of purposes, the way they can become beautiful records of our lives and contain nuggets of information – written, drawn, scribbled, stuck in – that may reveal their importance at any moment.

Just this morning, I posted the photo on the left during breakfast in Zanzibar. On the other side of the world, my Mum – an avid Bubble Catcher – remembered a sketch she had done from almost the exact same spot over 30 years beforehand. She dug through her many notebooks, found the sketch and sent it to me.

When that kind of thing happens, there is a definite magic to it.

And, I think, there is a magic to the Bubblecatcher concept.

As teachers, we continue to fabricate things for students to write about… and are still surprised when they are reluctant to write, when they can see right through the situation and realize there is no genuine reason to write. They are not fools, they know they are being asked to write “just because”. That justification went out of fashion years ago.

Bubblecatchers turn this situation around. Life is full of reasons to write that require no fabrication. When we give our students rich and varied experiences, when we put them in situations or contexts that are interesting or inspiring, when we empower them by helping them see that the things they do, the things they need to do and the things they have done are valuable and worth remembering… then writing them down makes perfect sense.

And, their Bubblecatcher is the perfect place to write them.

Next school year, I challenge all teachers to be like Anne and take their students on the Bubblecatcher journey. Take them somewhere to buy notebooks, or just give them a week or two to buy them in their own time (choosing their own is an important ingredient). Then, bring in the habit of jotting things down in them, of carrying them around to different learning experiences, of quickly writing to-do lists at the end of the day, of taking notes and quotes when watching a video, of doodling in them when there’s some time to spare, of pausing for a moment and recording how you all feel.

And, have your own Bubblecatcher so you are with them.

Don’t mark the writing, but also make sure it is not always private. Invite students to read things out sometimes. Model the enjoyment of the words, model the satisfaction of crossing out an item on a list, give them the beautiful sensation of having something they said become a quote that shifts your collective understanding.

Let your pedagogy create the bubbles… and then let the notebooks catch them.

P.S. a digital replacement is a cop-out, don’t kid yourself. A real Bubblecatcher doesn’t need charging.

Be careful with Seesaw

A friend of mine returned from Canada recently having been shocked by the proliferation of home-monitoring technology since his last visit and the number of his friends and family who now engage constantly in watching the goings-on in their houses while they’re out.

This really got me thinking about how the existence of new technology creates new habits and how this is true also of work. The developments in technology have led to different types of work and the fact that we can, and feel like we should, be working all the time. This isn’t a revolutionary thought, people talk about it all the time. However, I want to focus on one piece of technology, Seesaw.

The advent of Seesaw is exciting. It makes things possible that weren’t really possible before. In a nutshell, it is really the first way that teachers can do quick and easy documentation that is instantly shareable with parents who can see it using an app on their own devices.

Great! Right?

Well, not if you’re not really careful about how you use it.

You see, things that seem cool and different at first can quickly transform themselves into an expectation and therefore into work. If you’re not really, really purposeful about how you use Seesaw, it’s going to rapidly become a pretty pointless instant scrapbooking activity that gives parents a steady stream of images from within the classroom that they are going to depend upon but not necessarily learn anything from.

So, now you’ve got to deal with all of the massively important complexities of being a good teacher while also contend with providing a steady stream of posts that show everyone what you’re doing – basically classroom social media. Some people deal with this by handing responsibility over to the kids and calling it “agency”. But this, more often than not, leads to a steady stream of low-quality images or videos that are captured with little thought or purpose and that provide parents with little or no substantial information about the nature of the learning that students are engaged in. It also engages students in screentime that has little or no value. What’s more, it kind of feels like a gateway to the behaviours we see around us in society of having to post things on social media in order to prove they happened!

In your schools, put the following questions at the centre of everything you do with Seesaw:

When we post something on Seesaw, what are we communicating about the type of learning we value?

When people see what we post, what will they learn about the type of learning we value?

If you have some pretty good answers to these questions… proceed. If, however, your answers are “nothing” or “we’re not sure” or “we haven’t thought about it” then stop using Seesaw immediately and resume only when you have made some proper plans that will make it purposeful.

Part of those plans should involve making some BIG decisions about who your intended audience is for Seesaw:

- Is the intended audience limited to colleagues? Some schools have taken this approach to great effect and used Seesaw purely for pedagogical documentation that is then used to inform responsive planning sessions. Of course, you’re going to have to wrap some intelligent ways of working around this – mainly involving time.

- Are parents the intended audience? If so, make sure you are providing them with quality content that shapes their understanding about what education is, what learning looks like and what you are trying to achieve in your school, grade level or class. This is your chance to really have an effect on them – which of course can go either way!

- Are students the intended audience? If so, you will need to make some plans for how they will make informed decisions about what content to post and why, reflect on their content, how they will receive feedback on their content and how their content will be used as evidence of learning that will inform next steps. This is going to involve a lot of thinking tools and just-in-time instruction to guide them towards those habits and practices.

I’m going to stop here… I think that’s plenty of food for thought for now. Please give it some thought! I hate to see so much time being wasted on something that may be pointless, or even harmful.

Studio 5: It took more than 7 days

There is considerable hype around the Studio 5 model that is currently being piloted at the International School of Ho Chi Minh City… and rightly so. Studio 5 is a brave concept that doesn’t just pay lip-service to the philosophies upon which the IB Primary Years Programme and other student-centred, inquiry-based frameworks are built. It creates the conditions for all of that philosophy to become practice. Very rare.

Don’t be fooled though.

This stuff is not new.

Progressive and innovative educators have been doing some of these ideas for years. Schools have been designed around them. Movements have evolved around them. Books have been written about them.

But, these have either fizzled out, faded away, disappeared or survived as weird exceptions to the rule. Perhaps sustained by wealthy benefactors, enigmatic leaders or a powerful niche market.

Studio 5 is a wonderful example of what is possible. But it is critical that anyone hoping to move their school, or even just a part of it, towards a similar model must understand that Studio 5 didn’t just appear out of nowhere. It comes after four years of smaller, very significant, steps. Shifting mindsets, pedagogies, structures, systems, habits, priorities… incremental changes to these over a sustained period of time cleared pathways, opened doors and generated momentum.

Each change was a question that could only be answered by the next change.

Without this evolution, one in which the Studio 5 model was genuinely a natural progression, it would just be a novelty.

In a series of upcoming posts, I will reveal the milestones in the evolution of a school in which Studio 5 is possible. Perhaps these can provide tangible ways that other schools can begin to consider similar change, but change that is logical and natural in their context.

Being a PYP Teacher Part 4: Collaborate with your students

Kath Murdoch says that inquiry teachers “let kids in on the secret”, and I totally agree.

Far too often, we keep all of the planning, decision-making, assessment data, idea-generation, problem-solving and thought-processes of teaching hidden away from our students. Because of this, teaching becomes something that we do to students, not with students. As long as we are doing all of those things ourselves, behind closed doors, education will retain its traditional teacher-student power relationship and, no matter how often we use fancy words like “agency” and “empowerment”, students will continue to participate in, rather than take control of, their learning.

PYP teachers take simple steps to “let kids in on the secret”, to collaborate with their students.

They begin by showing students that their thoughts matter – they quote them, they display their words, they refer back to their thinking and they use their thinking to shape what happens next. When students become aware that this is happening, their relationship with learning instantly begins to shift.

Then, PYP teachers start thinking aloud – openly thinking about why, how and what to do in front of their students and not having a rigid, pre-determined plan or structure. This invites them into conversations about their learning, invites negotiation about how their time could be used, what their priorities might be and what their “ways of working” might be. There is a palpable shift in the culture of learning when this starts happening, from compliance to intrinsic motivation.

Finally, PYP teachers seek as many opportunities as possible to hand the thinking over to their students deliberately – not only because they have faith in them, but also because they know their students are likely to do it better than they can themselves! It’s shocking how frequently we make the assumption that students are not capable of making decisions, or need to be protected from the processes of making decisions, or that getting them to make decisions is a waste of “learning time”. As soon as we drop that assumption and, basically, take completely the opposite way of thinking… everything changes. Hand things over to them and they will blow you away! I still love this video of my old class in Bangkok figuring out the sleeping arrangements for their Camp and doing it way better and with more respect than a group of adults ever could!

So… today, tomorrow, next week… look for ways to let kids in on the secret, and let us know what happens as a result!

Being a PYP Teacher Part 3: Know your students

Bill and Ochan Powell (rest in peace, Bill) always say, above all else, “know your students”.

The written curriculum in your school is the students’ curriculum.

Your curriculum is the students.

They are learning about all the things expressed in their curriculum (and hopefully much more!).

You are learning about them.

Understanding this will help you make the shift from “deliverer of content” to a facilitator of learning, a designer of learning experiences and a partner for each of your students as they learn and as they navigate their curriculum. Each day, you will arrive at work full of curiosity, poised and ready to:

- get to know your students better

- inquire about them

- research into them

- get a sense of who each of them is in the context of learning taking place at the time

- discover what motivates them

- find out what interests and inspires them

- help them develop their own plans for learning

- get a sense of what they can do and what skills they may develop next

- learn about how they think

- try a wide variety of strategies to do all of the above

- never give up…

It is a very exciting moment when PYP Teachers realise they are inquirers who are constantly seeking, gathering and using data (in it’s most sophisticated and powerful forms) about their students.

It is this realisation that sets apart genuine PYP Teachers from those who simply work in a PYP school, for the two are vastly different.

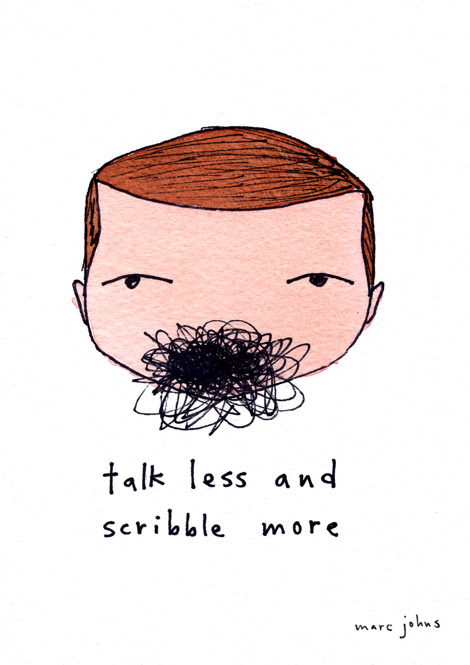

Being a PYP Teacher Part 2: Talk less, ask (and scribble) more

I’ve borrowed the inspiration for this one from two important sources, Kath Murdoch and Inquiry Partners.

PYP Teachers need to be determined to allow their students’ voices to dominate discussions in the classroom, and to use strategies that promote the thinking that is necessary for that to happen. They use open-ended questions or problems that invite debate, differing perspectives, controversy, elaboration and uncertainty… and then they listen, they probe and they invite others to add their thoughts. Most of all, they are curious about what students may be revealing through their words and how they might be able to use that information to guide what happens next.

The traditional “whole class conversation” tends to be between the teacher, who controls the conversation, and the one student doing the thinking at the time. There may a few others listening and waiting to contribute, but there will also be some who have drifted off, who have stopped listening and who may just be waiting for it to be over.

Simple strategies like “turn and talk” or “chalk talk” set things up so everyone is doing the thinking at the same time, not just one person at a time. Asking students to record their thoughts in writing also ensures they’re all doing the thinking, and sets them all up to be able to contribute to discussions afterwards.

More complex approaches, like Philosophy for Children and Harkness, model and teach the art of conversation and invite students to participate in deep conversations in which all are equal members.

The most simple strategy though is simply to remember to talk less. Say less at the beginning of lessons. Only repeat instructions to those who need the instructions to be repeated. Even better, display instructions or processes visually so that those who are ready and able or get on with it can do just that. You’ll be amazed how much time – a precious commodity in schools – can be saved.

Some of that time, of course, is yours… and it can be used to redefine your role as a teacher. Rather than doing so much talking, you can be observing students, listening to them, taking notes, writing down quotes that come from their mouths… all of that scribbling is formative assessment, planning, affirmation and honouring the importance of things your students say. It is inevitable that the teaching that follows will be different as a result.

Being a PYP Teacher Part 1: Carry the Book

The 1st, 50th, 500th and 5000th step required in order to become a PYP Teacher – because this is a never-ending process – is to carry a copy of Making the PYP Happen with you at all times.

Don’t go to any planning meetings without a copy of Making the PYP Happen. Instead, always have it with you so that you can:

- refer to it for guidance as you strive to make your planning purposeful

- refer to it to remind you of the five essential elements of the PYP

- refer to it for ways to make learning rich in possibilities

- refer to it so that you can ensure you really are educating the “whole child”

- refer to it so that you understand why, how and what to assess

- refer to it to seek clarity and the eloquent description of learning in its various forms

- refer to it so you can become familiar with how education is changing, and has been changing since 2009

Whenever I ask people where their copy of Making the PYP Happen is, in lots of schools, the responses frequently vary between:

- “Oh, I have one somewhere”

- “Umm… I have a digital copy, I think”

- “Yep, it’s on my laptop. Let me just load it up”

- “I don’t know where it is”

- “Ha ha ha, I don’t keep one with me all the time!”

These responses are indicative of a school culture in which reference to the most important guiding document has not become a habit. This makes it a thousand times less likely that people will know what it says, and then this makes it 1000 times less likely that people will be able to make it happen.

Naturally, the reverse of this is equally true.

So, go on. Find your copy, or get one printed if you don’t have one (digital just ain’t good enough, my friend) and take it with you to all planning sessions. Having it there for reference, for inspiration and for guidance will empower you as you seek to become a better and better PYP Teacher.

I just hope that the enhanced PYP doesn’t bring with it the removal of this amazing resource. In fact, I hope it brings quite the opposite.

Assessment. Tests. Exams. Assignments.

Simon Birmingham is the Education Minister for Australia. He has recently announced plans to introduce “light-touch assessments’ for Grade 1 students.

Click HERE for the article in the Sydney Morning Herald (18 September 2017) for more on this, to bring you into the picture.

What are we doing to our kids?

More assessments. More data. Something has to give. What about giving our kids a chance to come into their own, in their own time. Teachers already collect copious amounts of data every moment of every day.

When are we going to stand up and say enough is enough? Schools are feeling more like laboratories in the way of factory farming, mass producing 1 dimensional teaching – what about learning?

Our students have just been through a week of testing. One of the external assessments used here is…. Measures of Academic Progress (MAP). We are constantly testing our kids. Analyzing the data and then trying to figure out a way to make sense of it. If a student is a good test-taker, they will make it just fine.

The truth is….. in my opinion at least, where is there room for meaningful planning, best practice and valuing real learning beyond a test or book. We have more data than we know what to do with. Teachers are already on the edge, just keeping up.

I believe there is a place for this….. a very small place. We need to slow down a little, back off, and allow our teachers to be creative so they are designing the most powerful learning experiences. Not churning through pages and pages of graphs and numbers and percentages.

I’m I the only one that is feeling this frustration? What is your stance on this matter?

Let’s not allow a raw number shape and define our kids’ self-esteem and confidence at such an influential age.

We need to be pulling good people into the profession. Teaching is such a thrilling and invigorating career path. We have a privileged role in society that is incredibly fulfilling. We need to let good teachers get on with it, and trust that good learning is happening. Invest in that, not more assessments. We are heading down a road of burnt-out and stressed-out teachers. This makes me want to remain in international schools – we are very fortunate to be in our unique situation, where we carefully think about what is important and have a voice in determining our path.

I don’t actually think people know when or how we will ever usher in an ‘educational revolution.’ I’ve just felt ripples of good educators, trying to challenge the status quo, in their own way, within their control. Where to from here?

Designing powerful learning experiences

Once teachers have a good sense of the “big picture” of units, they turn their attention to designing the initial learning experience, or provocation, for their students. Not much more than this should be planned as everything else really depends on how students respond to this initial experience.

When designing powerful learning experiences, it is important to consider these points:

Check teacher attitudes – all teachers involved need to be genuinely curious about their students and how they will react or respond to learning experiences and see themselves as inquirers who are researching their students.

Return to learning – continuously remind yourselves of the desired learning in the unit and also be aware of any other learning that may unexpectedly become part of it.

Know your curriculum – familiarity with the curriculum – basically “knowing it like the back of your hand” – means you can plan for learning and also include unexpected learning as it arises.

Understand difficulty and create struggle – students will only really reveal useful information about themselves to you if there is an element of challenge or struggle involved. This is what separates a provocative learning experience from an “activity”.

Consider group dynamics – be very purposeful about how you intend your students to work… are you looking for them to think independently or to collaborate? Are their choices about how to work part of the information you’re looking for?

Collaborate for effectiveness – work well with your colleagues to make sure each of you has an active role during the experience, such as observing and documenting in different ways.

Test on yourselves – it’s always a good idea, as well as fascinating, for teachers to try out a learning experience on themselves to see how it feels, what is revealed and whether or not it is really worth doing.

Use pace, place and space – these three elements are often overlooked, yet can totally make or break learning experiences. Think carefully about how time will be used and how you can read the situation to add or take away time accordingly. Think carefully about the best location for learning experiences to take place and how that location could be adapted for the purpose. Explore the space and discuss how you can use space intentionally, including the movement of students and the placement of materials, to create the right feeling and atmosphere.

Understand the power of mood – explore ideas and strategies for the creation of particular moods to enhance learning, such as relaxation, mindfulness and music (I’ll write a posting about this soon). Most importantly of all, have high expectations for student attitude and let them know you care about it and take it seriously.