Category: Transdisciplinary

Why Bubblecatchers Matter

A few days ago, My family and I went for dinner at Anne’s house. Anne was one of my Mum’s closest friends when we lived in Tanzania in the 80s, and I haven’t seen her for 31 years. During the evening, I spotted a very nice notebook on the coffee table in front of us… “nice Bubblecatcher” I said.

“Ooooh yes… Bubblecatchers!” Anne replied with incredible enthusiasm.

It turns out that, for many years, Anne has shown her students at the International School of Tanganyika – and her students in the school she works in now – the video of my Learning2 talk in which I shared the story and concept of Bubblecatchers.

As we talked about how she has used them, I was reminded – again – of their profound importance, of the many nuanced habits that they encourage, of the way they can change and enhance relationships with writing for all sorts of purposes, the way they can become beautiful records of our lives and contain nuggets of information – written, drawn, scribbled, stuck in – that may reveal their importance at any moment.

Just this morning, I posted the photo on the left during breakfast in Zanzibar. On the other side of the world, my Mum – an avid Bubble Catcher – remembered a sketch she had done from almost the exact same spot over 30 years beforehand. She dug through her many notebooks, found the sketch and sent it to me.

When that kind of thing happens, there is a definite magic to it.

And, I think, there is a magic to the Bubblecatcher concept.

As teachers, we continue to fabricate things for students to write about… and are still surprised when they are reluctant to write, when they can see right through the situation and realize there is no genuine reason to write. They are not fools, they know they are being asked to write “just because”. That justification went out of fashion years ago.

Bubblecatchers turn this situation around. Life is full of reasons to write that require no fabrication. When we give our students rich and varied experiences, when we put them in situations or contexts that are interesting or inspiring, when we empower them by helping them see that the things they do, the things they need to do and the things they have done are valuable and worth remembering… then writing them down makes perfect sense.

And, their Bubblecatcher is the perfect place to write them.

Next school year, I challenge all teachers to be like Anne and take their students on the Bubblecatcher journey. Take them somewhere to buy notebooks, or just give them a week or two to buy them in their own time (choosing their own is an important ingredient). Then, bring in the habit of jotting things down in them, of carrying them around to different learning experiences, of quickly writing to-do lists at the end of the day, of taking notes and quotes when watching a video, of doodling in them when there’s some time to spare, of pausing for a moment and recording how you all feel.

And, have your own Bubblecatcher so you are with them.

Don’t mark the writing, but also make sure it is not always private. Invite students to read things out sometimes. Model the enjoyment of the words, model the satisfaction of crossing out an item on a list, give them the beautiful sensation of having something they said become a quote that shifts your collective understanding.

Let your pedagogy create the bubbles… and then let the notebooks catch them.

P.S. a digital replacement is a cop-out, don’t kid yourself. A real Bubblecatcher doesn’t need charging.

Being a PYP Teacher Part 1: Carry the Book

The 1st, 50th, 500th and 5000th step required in order to become a PYP Teacher – because this is a never-ending process – is to carry a copy of Making the PYP Happen with you at all times.

Don’t go to any planning meetings without a copy of Making the PYP Happen. Instead, always have it with you so that you can:

- refer to it for guidance as you strive to make your planning purposeful

- refer to it to remind you of the five essential elements of the PYP

- refer to it for ways to make learning rich in possibilities

- refer to it so that you can ensure you really are educating the “whole child”

- refer to it so that you understand why, how and what to assess

- refer to it to seek clarity and the eloquent description of learning in its various forms

- refer to it so you can become familiar with how education is changing, and has been changing since 2009

Whenever I ask people where their copy of Making the PYP Happen is, in lots of schools, the responses frequently vary between:

- “Oh, I have one somewhere”

- “Umm… I have a digital copy, I think”

- “Yep, it’s on my laptop. Let me just load it up”

- “I don’t know where it is”

- “Ha ha ha, I don’t keep one with me all the time!”

These responses are indicative of a school culture in which reference to the most important guiding document has not become a habit. This makes it a thousand times less likely that people will know what it says, and then this makes it 1000 times less likely that people will be able to make it happen.

Naturally, the reverse of this is equally true.

So, go on. Find your copy, or get one printed if you don’t have one (digital just ain’t good enough, my friend) and take it with you to all planning sessions. Having it there for reference, for inspiration and for guidance will empower you as you seek to become a better and better PYP Teacher.

I just hope that the enhanced PYP doesn’t bring with it the removal of this amazing resource. In fact, I hope it brings quite the opposite.

Time Space Education Podcast #1 – Our Purpose

In this, the first ever Time Space Education Podcast, Chad, Cathy and Frank and I discuss the purpose of our work and what our professional focus is at the moment. Naturally, however, we drift into lots of other

https://drive.google.com/file/d/0BwlE-dHEWo4ESExyZTYzbEJtX28

When kids are doing, modern teaching kicks in

We have a Grade 5 teacher who is very new to the PYP. He joined us after witnessing Grade 5 students last year in the middle of the PYP Exhibition. When he saw all those students heavily involved in a wide variety of unique projects, all operating at their own pace, making their own decisions, creating products, figuring out budgets and so on… he became very excited about the opportunities the PYP provides for students as well as for teachers with a modern mindset.

During the first half of the year, however, he has been quite frustrated. There was something about the units of inquiry that made them heavily teacher-directed and leaned back towards more traditional day-to-day teaching. He was waiting for those times when students would walk into school each day knowing what they were working on, how they were going to go about doing it and why it mattered. I could see he was questioning whether or not the PYP really is what it pretends to be!

Now, however, he is clearly feeling as though both his students and he are in that place, that sweet spot in which students are doing and in which his role as their teacher has shifted to being a “consultant”, a person who assists them with their plan rather than trying to get them on board with his.

This is a bit of an allegory of the struggle many teachers, and teaching teams, have to create the conditions for students to be working in this way: to have figured out a focus, to have developed a plan, to be sourcing their own information, resources and mentors, to be making their own decisions and to be coming in to school each day motivated and ready just to get on with it. All too often we hold them back, or we confuse or demotivate them by over-teaching, or we don’t let them go because we don’t really understand what it is we’re trying to get them to do, or because we fear being out of control or… worst of all, because we don’t trust them or believe they are capable.

For modern, student-centred, inquiry-based pedagogy to even begin to dominate our weekly schedules, we need to help our students go through the following process quickly enough to allow them the time to start doing and to be able to go into enough depth with that for genuine and powerful learning to come out of it:

- help them understand the context of the learning

- help them think about the context in diverse, rich and deep ways

- help them filter all of that thinking in order to develop their own interest area and focus

- help them figure out what they want to achieve within that focus

- help them get started in order to achieve it

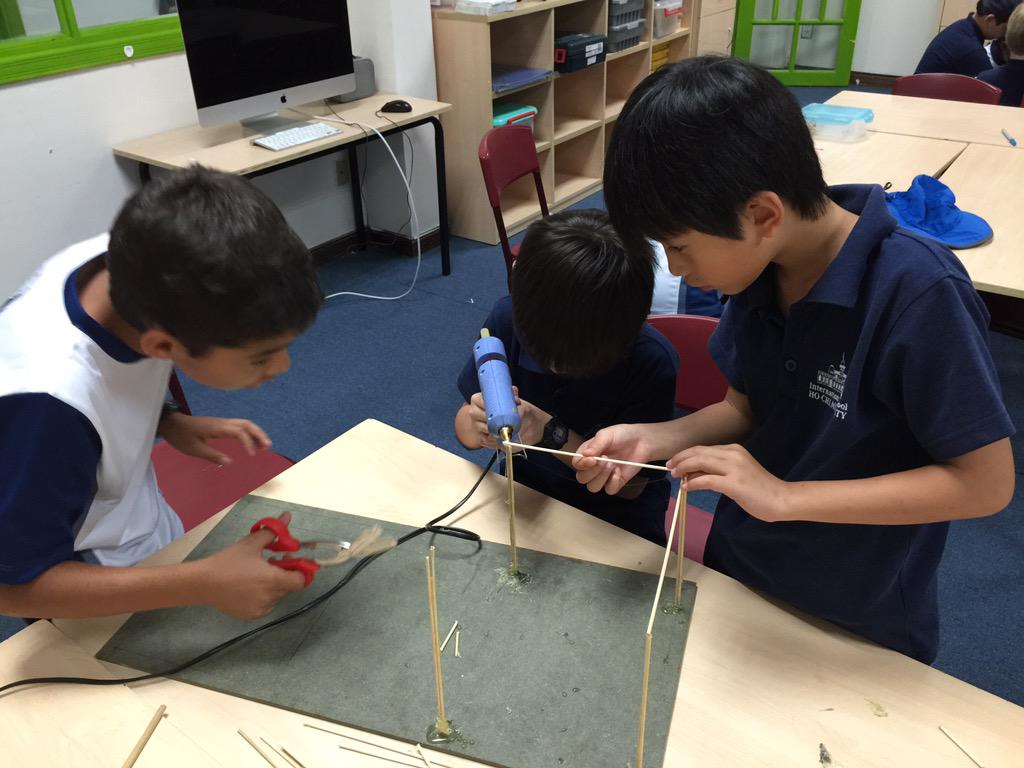

Creating the need or desire to make

There’s a lot of hype around “makerspaces” at the moment – I definitely wish I’d bought shares in Lego a couple of years ago! It’s great though, our schools are responding to the need for students to work with their hands, to think differently and to learn to become content or product creators.

One thing we have to be very careful of, however, is that theses places – and what happens inside them – don’t become another separate entity, another “subject” or another thing that happens outside of “regular learning” or “the real stuff”. Know what I mean?

These spaces – and what happens inside them – need to become natural extensions of all the other types of learning that happen in our schools. All of that learning needs to create opportunities for students to make. Students need to become more and more aware of what is possible and then they need to be connected with the people, places and materials that can make those possibilities become reality.

True change happens when making becomes a mindset in the school, not a subject. If the mindset doesn’t evolve, makerspaces may end up being another fad.

Redefining School – The Real World School

You know how people often say “school is their real world” when you start talking about “out there in the real world”? Its not true, school isn’t our students’ real world. It is a social construct, designed and managed by adults. It isn’t their real world, but it is their existence.

Schools and the real world are leagues apart. Schools are bubbles. So when we say it is “their real world” we are actually talking about a sanitised, protected, censored, authoritarian enclave that they inhabit for the first 18 years of their lives.

There’s so many angles that this posting could take at this point. However, today I want to write about how we protect our students from reality in the belief that this is what is best for them, and how we might be able to change that.

If we are honest, the real world is not a very nice place. Sure, there’s lots of positive stories and wonderful people. But, in general, the world is not a very nice place. This is reflected in the fact that most school mission statements give themselves and their students the unenviable task of making the world a “better”, “happier”, “peaceful” or “harmonious” place for future generations. We wouldn’t be saying we need to do that if the world was wonderful now, would we?

But, can we honestly say that our students are emerging as people with a conviction and a determination or even an awareness of how things need to change? Are we bringing the harsh realities of the world into our curriculum and provoking our students to think critically, cynically, divergently and alternatively? Correct me if I’m wrong, but probably not.

For example, how many schools are using the war in Syria and the huge exodus – and rejection – of people as a way to develop empathy or to learn about the evil acts mankind is capable of? If not, how can we possibly believe that history won’t continue to repeat itself? What stops us from doing that? Is it the sheer quantity of other stuff that “must be covered”? Is it the fear of taking a stance that may offend someone or other? Is it a desire to be so impartial that we end up standing for nothing at all?

I wonder how many genuine learning opportunities happen out there in the real world that could be deeply explored, that would evoke genuine emotional responses and provoke progressive thinking in our students?

Imagine a curriculum that is shaped by what is happening in the real world. Imagine a school that allows its curriculum to be shaped by what is happening in the real world.

Its not that complex, really. As we all know, learning is at its most powerful when it moves from facts to knowledge to conceptual understanding. Well, those initial facts and areas of knowledge can easily be determined by what is going on in the real world – whether its the horrific and the heart-breaking or the uplifting and the awe-inspiring. Connections can be made with other events in time or space that can lead to real understanding… so your starting point is flexible. Flexible enough to be topical, real, emotive and empowering.

I work in a PYP school and we are coming up to our annual curriculum review. One of the lenses I will ask teachers to scrutinise our curriculum through will be “The Real World”. Are there real-world starting points for each of our units of inquiry? Are students able to apply what they learn to real-world situations?

Now, don’t get me wrong. I am not suggesting we burden our young people with the onerous task of righting all our wrongs and saving the planet! I am, however, asking if we should be making sure as much learning as possible is centred on things that are really happening.

When we’re interrupting them we know it’s working

I have just been in our Grade 2 classrooms. In our school we often talk about the “flow” of inquiry, the “momentum” of inquiry and how we can create the conditions for those in our “units” of inquiry.

What I just witnessed in Grade 2 tells me that they are currently creating those conditions. Students are so involved in what they’re doing that we, with our timetables, starting and finishing times and other agendas are literally interrupting them. We are breaking their flow. We are stopping their momentum.

And that’s fantastic!

These are 7/8 year old children. They have been through a process of reflecting on their lives so far, their strongest memories, the emotions they associate with those memories, choosing which memories to focus on, considering different forms of expression and selecting which form of expression to use to share stories about their memories. Pretty complex, eh?

Now, they are in varying stages of putting together their works of art – dances, paintings, drawings, lyrics, animations… all sorts. When you walk into any of their classrooms – which have actually evolved into art studios – you are immediately struck by the variety and the palpable atmosphere of purposeful activity.

Some of the students are not in their classroom. Some are in the PE department using the space and getting advice on choreography from PE Teachers. Some are in the Art room using materials and getting advice from the Art Teacher. Some have gone to the music room to seek out guidance on song composition.

Learning should look like this a lot of the time. Students accessing the variety of spaces and expertise that schools possess. Students working on something that is highly motivating and of their own design. Teachers working as connectors, advisers, referrers and consultants.

And, most of all, students should be disappointed when they have to stop what they’re doing… that’s when you know they mean it!

Even better though, would be greater flexibility so that those interruptions happen less.

Student-created learning is the key to inquiry

Inquiry-based learning remains a mystery to many teachers, and a serious challenge to others. Creating the conditions for our students to be intrinsically motivated while still addressing important areas of curriculum is not easy.

Or, is it?

Maybe, we just have to readjust our expectations, like…

- expecting all students to be working on the same curriculum areas at the same time

- expecting all students to be interested in the same things at the same time

- expecting all students to move through an inquiry “process” or “cycle” at the same time, and with the same momentum

Once we get ourselves out of these habits of expectation, we can free ourselves up in order to free our students up. Once we do that… then we can set out to create the time, the space and the conditions for students to be able to design their own learning.

This, of course, is another crossroads… and another point where teachers become lost:

- they struggle with the openness of the idea of students designing their own learning

- they struggle with their own judgments of the value of what students are interested in

- they struggle with the identification of learning connections

- they struggle to see the potential for where students may take their ideas

- they struggle with strategies to help students who have no idea what they want to do

- they struggle with the redefinition of their role that is so crucial (more on this in the next posting)

Very often, these struggles become the reason not to pursue student-created learning. It goes in the “too hard basket”. But, these struggles should be the justification for pushing forward with it, because these struggles symbolize what it means to inquire, they represent the efforts needed to nurture students who are inquirers, they are the inner battles we must face in order to drop our tendency to teach too much!

For those of us who push forward with it… this is what it could lead to.

Imagine a classroom full of students who have all had the chance to design their own learning (this might only be for a section of a day each week, or maybe a whole day every week… or more!). Imagine them all working on very different things – building a prototype of something they have designed, researching the existence of planets beyond our solar system, cutting fabric to create a dress, mixing ingredients for a new recipe, writing the seventh chapter of a book, conducting experiments with light.

The potential list is endless… because our students (if we allow them to reveal them to us) have endless interests, curiosities and dreams. Usually, the only thing stopping them from learning about them is the person in charge of their learning, or the institution in which they learn. But if we can reverse that, let them bring these interests, curiosities and dreams into our schools and let them pursue them… the learning that happens as a result is unprecedented.

If we know our curriculum well enough, we can make a myriad of connections for our students, we can help them see all sorts of ways in which they are learning what we would normally have had to teach them. We can use our curriculum to help them figure out where to go next… the curriculum becomes our friend as it reveals possibilities rather than reminding us what we have to cover.

Its just not going to be all the same areas of the curriculum, at the same time and at the same pace.

But, who really believes learning works that way anyway?

Jane Goodall explains “Action” pure and simple

“Action” is the most abstract of the PYP Essential Elements. We know it’s there, we know its important, we know its designed to encourage students to do good things… but we so often misinterpret it, forget about it and trivialize it.

Jane Goodall’s quote, below, puts it in the most simple terms. Students (and teachers) need to see how everything they do represents their “actions” and that reflection on what they do helps them to consider the difference – either good or bad – that their actions make. This could range from putting their shoes away when they get home to reaching for a book instead of an iPad to helping a friend with a problem to noticing a child beggar and mentioning it to a parent to… the list goes on.

Our problem, very often, is that we narrow down what “action” means so much that it has little or no value. Are we surprised, then, that so many of our students go through school believing it is a bake sale?

How do you guide your students towards a sophisticated understanding of Action?

Mindfulness and Intention

Mindfulness practice creates a mood, and skillful educators use that mood to help students be at their best.

Often, the mood that is necessary is one of independence, self-management and self-direction. I find it effective to give students a decent 10 minutes of mindfulness practice. Then, in the final stages of that practice, I ask them to consider what their intentions are for the time that follows. What will they try and achieve? What do they need or want to do?

We work towards being very detailed in the description, so rather than say “I will work on my project” they give specific details like “I will research how to split video files so I can edit my movie”. As you can see in this video, some of the students are quite specific and yet others are very vague. With regular practice, they would all be outlining their intentions with more detail.

This sort of strategy not only creates a mood and helps students be self-directed, it also gives the teacher a big picture of what stage each student is up to with the things they’re working on and how organized they are. In this sense, it is also a formative assessment. After the session in this video, I knew exactly which students I needed to give some time to and follow up with.